Lymphedema and lymphatic cording are both commonly overlooked treatment complications of breast cancer treatment. Both are linked to the lymphatic system, can cause discomfort and pain, and can limit the functionality of the affected limb. However, they are quite different in nature. Current literature reports no connection between cording and lymphedema1 2. Recent studies report a higher incidence of cording (30% 3) compared to lymphedema 21.4% 4.

Lymphedema and lymphatic cording are both commonly overlooked treatment complications of breast cancer treatment. Both are linked to the lymphatic system, can cause discomfort and pain, and can limit the functionality of the affected limb. However, they are quite different in nature. Current literature reports no connection between cording and lymphedema1 2. Recent studies report a higher incidence of cording (30% 3) compared to lymphedema 21.4% 4.

In this blog, we will discuss the causes, symptoms and treatment options for breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) and lymphatic cording. We will also be highlighting some innovative research being conducted to better understand these breast cancer treatment side effects.

What is the lymphatic system?

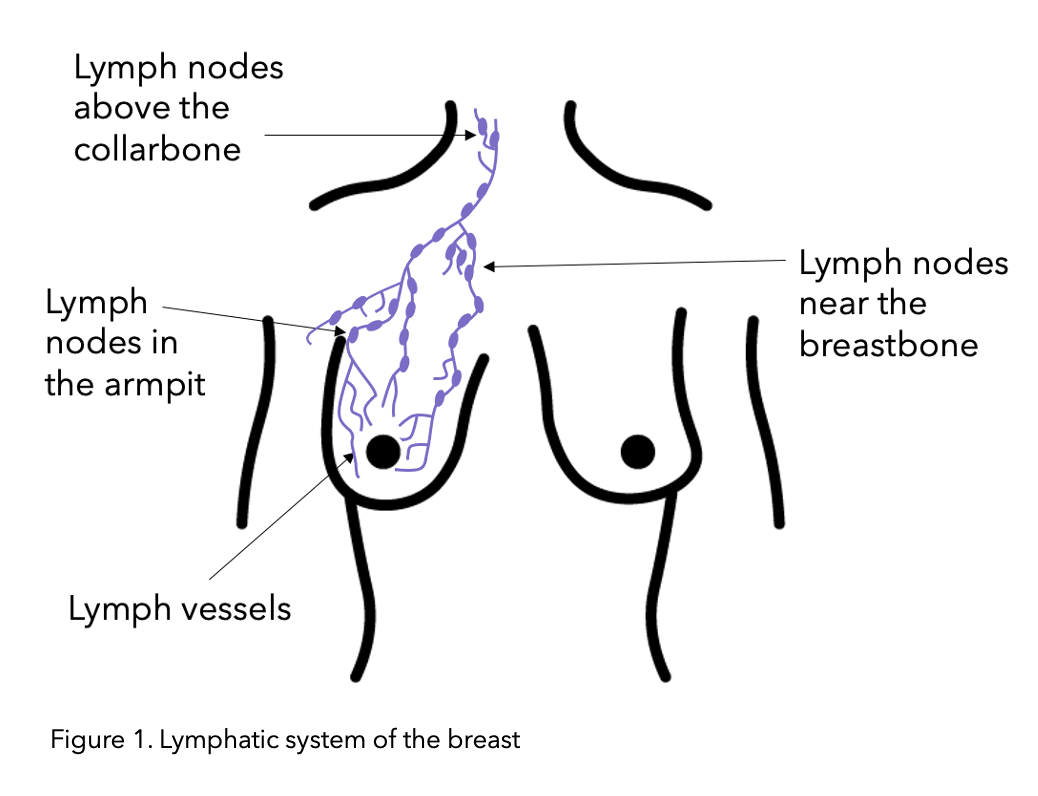

The lymphatic system drains key fluid called lymph from around the body via the lymph vessels (See figure 1 below). The lymph fluid contains the immune T and B lymphocyte which are white blood cells. This is why the lymphatic system contributes to the proper functioning of the immune system (the body’s defence system) for fighting off infections. The lymph nodes are small bean-shaped structures along lymph vessels that filter, store and release lymph fluid. Lymph nodes also referred to as glands, develop along lymph vessels and are often found in groups. Important lymph node groups are located in the neck, underarm, mediastinum, abdomen, pelvis, and groin 5 and are also present in breast tissue.

Figure modified from Macmillan.

Lymphedema

Lymphedema is a chronic condition involving the lymphatic system resulting in swelling of soft tissue. The number of people that experience lymphedema varies, and it depends on the extent of breast and axillary surgery, as well as adjuvant radiotherapy 6. Although reported in about 20% of breast cancer patients, breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) is a largely overseen side effect of breast cancer treatment 7.

What are the symptoms of lymphedema?

- Your breast, arm or other parts of your upper body has a little swelling at first but gets bigger over time.

- Early signs can be clothing or jewellery such as rings and watches feeling tight

- The skin in that area feels tight and sometimes has a tingling sensation.

- The arm / affected area feels heavy.

- Trouble moving a joint in the affected area (eg shoulder)

- The skin looks thicker or leathery (induration)

Lymphedema is a progressive condition. It is important to contact your healthcare team as soon as you notice symptoms so they can be managed as quickly as possible to reduce the advancement of lymphedema.

Using the free OWise breast cancer app, you have access to a secure diary where you can store notes, sensitive photographs and even audio recordings to track your progress and any visual changes. You can share these with your healthcare team or show them during an appointment.

What is the cause of lymphedema?

The swelling is due to a buildup of lymph fluid in soft body tissue caused by blockage or damage to the lymphatic system, preventing drainage. The lymphatic system can be blocked by a tumour, or damaged by cancer treatments such as surgery (nodes can be fully removed if they are cancerous, partially removed or accidentally damaged in the surgical procedure) or by radiotherapy. Radiation treatment can damage lymph vessels and can cause scar tissue that can block vessels.

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), also referred to as clearance, is when multiple or all lymph nodes are removed. In breast cancer surgery, this is mostly nodes from the armpit. If cancerous cells are found in multiple nodes it is likely you will need an ALND.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) carries lower risk of lymphatic complications as it can result in the removal of a few of the first nodes of a group. This affects the draining and functioning of the gland group less than an ALND procedure.

Risk of lymphedema increases as the amount of nodes are removed. A recent meta-analysis reported a 3-4 times greater rate of lymphedema among patients with axillary dissection than among patients with SLNB2.

Lymphedema diagnosis

Diagnosis can be carried out by comparing the size of the affected area to the non-affected counterpart. For example the circumference of the affected and the non-affected bicep. The rule of thumb is 2cm or 5% volume change between time intervals or difference between areas. 8, 13

Imaging tests can also be used to help diagnosis. These can include:

- Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound scans can be used to image the affected area and investigate where and why a blockage may occur.

- Lymphoscintigraphy (also used in SLNB) is a method in which a small amount of radioactive material is injected into the bloodstream and tracked to follow fluid flow and understand where the issue and/or blockage is located.

Stages may be used to diagnose lymphedema

Stage 0 (subclinical/latent): No clinical (visible) symptoms, but abnormal lymph movement. At this stage lymphedema can be established by lymphoscintigraphy. You can be at stage 0 for months or years before clinical or pain symptoms develop.

Stage 1 (mild): Early edema, lymph fluid starts to accumulate in the soft tissue (0–20% volume excess9). When applying pressure to the affected limb a temporary dip will form (pitting edema). Elevation of the limb resolves the swelling. With appropriate treatment lymphedema can be reversible at this stage as minimal/no permanent tissue damage has occurred.

Stage 2 (moderate): Swelling does not resolve with elevation and no dent is created by applying pressure. Changes to the skin and under the skin, such as fibrosis (thickening and hardening of skin due to tiny scar like structures caused by the protein-rich lymph fluid which is stagnant/not draining). The stagnant fluid also increases risk of tissue inflammation and infection. At this stage permanent tissue damages have occurred, treatment can help manage the lymphedema and prevent spread and deterioration. (21–40% volume excess9)

Stage 3 (severe) (lymphostatic elephantiasis): This stage is rare in breast cancer patients (41–60% volume excess 9).

What can I do?

There are many management strategies available, both conservative and operative. They aim to reduce the swelling, relieve symptoms and prevent lymphedema from progressing further by improving/facilitating the drainage of lymph fluid.

Conservative treatments:

- When possible elevate the affected area above your heart

- Refrain from wearing tight clothes or jewellery that could prevent blood and fluid flow

- Heat and sunburn can increase risk, stay cool and always wear SPF

- Education on infection prevention – skin hygiene

- Exercise: light movements help drainage. Your healthcare team will advise you of which exercises to do at which stage of your recovery, specific to your surgery and possible adjuvant therapies.

- Compression sleeve and or vest: The compression helps the fluid flow and drain through the affected areas.

- Controlled compression therapy

- Stage 1 Short stretch bandage applied by lymphedema specialist

- Stage 2 when the desired reduction is reached you can switch to a compression garment during the day, allowing for more mobility. Short-stretch bandages are still recommended at night time8

- Manual lymphatic drainage (MLD): A massage that stimulates lymph flow to proximal (near) normally functioning/draining areas to move fluid away from congested lymph vessels. ICG studies (injecting a substance to follow fluid movement) indicate MLD does enhance lymphatic flow. 8, 10

- Weight loss: Being overweight can exacerbate lymphedema. Your healthcare team will inform you if this is an issue.

Complete Decongestive Therapy (CDT), the standard management for lymphedema, consists of three principles: exercise, compression and skin care. CDT is typically broken down into two stages. Beginning with compression bandages, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) and specific exercises followed by MLD. The second stage consists of low resistance short-stretch compression bandages which increase lymphatic drainage. Studies have demonstrated CDTs ability to enhance lymphatic contractility, 8, 11 (the vessels ability to open and close) which would increase lymphatic flow, easing the buildup of fluid and thus swelling. Comprehensive studies have shown an increase in quality of life12 and an average decrease in swelling of 50%. 28. 29

“When a BCRL patient attends, I tend to treat pain before I progress to treating the lymphedema. Chest wall pain in patients who have received radiotherapy is common. I treat it very successfully using manual lymph drainage, using a particular technique of ‘stationary circles’ from the Dr Vodder technique. The principal of its use is stretching fascia gently.” – Monica Conway, Manual Lymphatic Drainage Specialist

CDT can be challenging to receive as it requires multiple healthcare providers and is labor-intensive. Do not worry if you can not access full CDT, the treatment components are also very effective even when not following the CDT structure. Studies have shown that compression garments reduce volume by 31% 14 and controlled compression therapy by 46%. 15

Whatever the treatment plan you and your healthcare team have decided on, it is important to follow it and discuss any changes with your healthcare team.

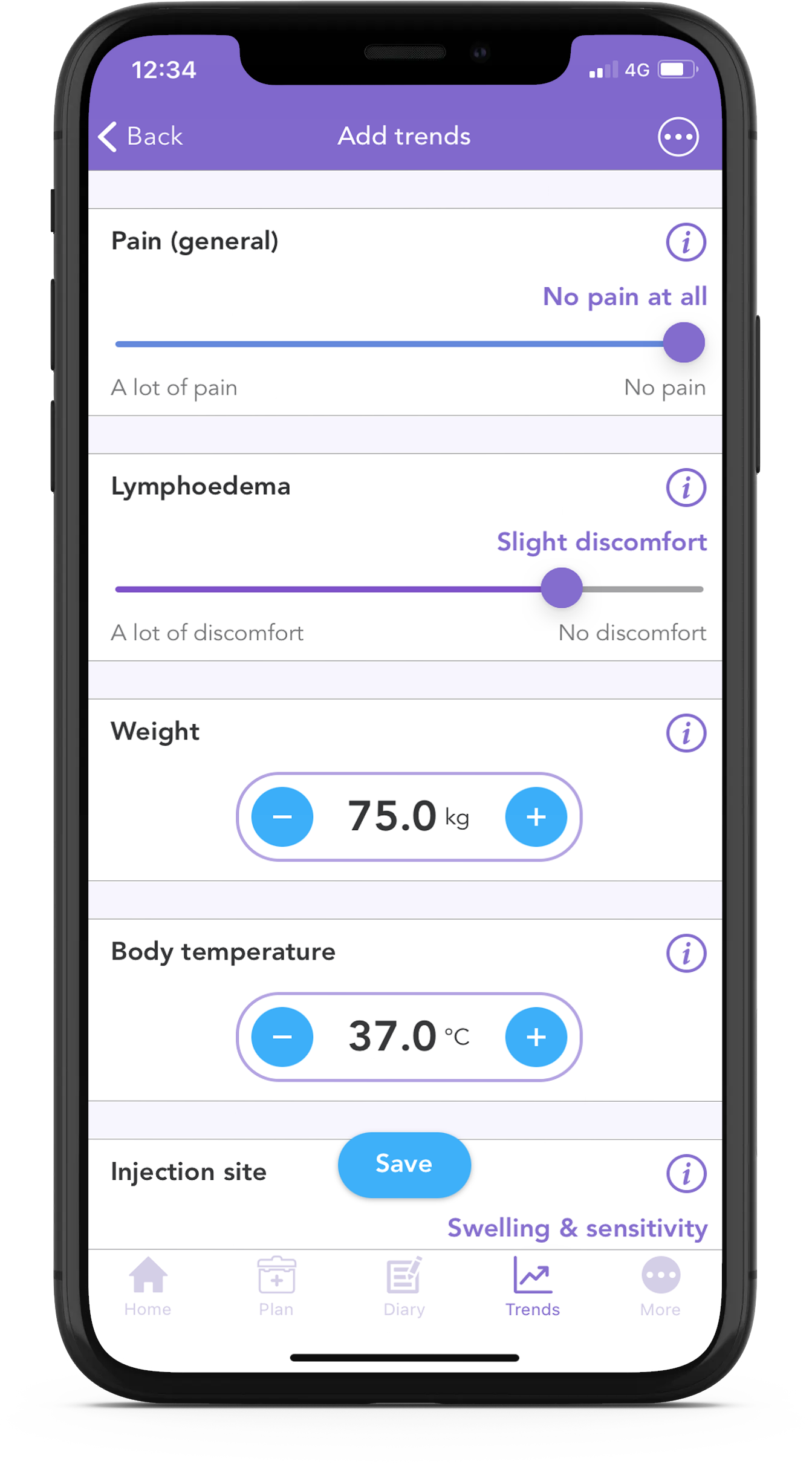

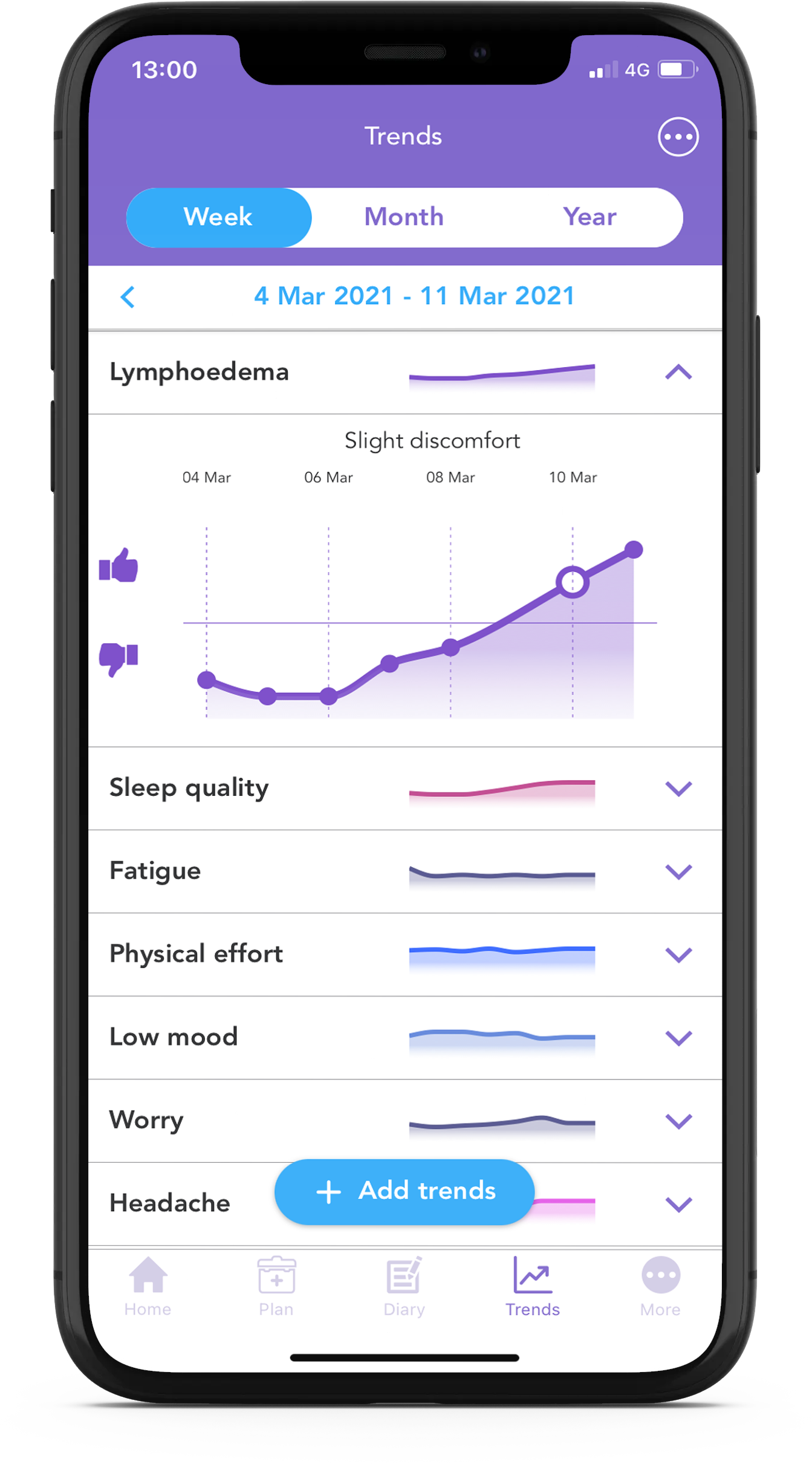

With the free OWise breast cancer app, you can track your lymphedema discomfort daily using the trend sliders.

If conservative management methods are ineffective operative methods are available.

Operative management options:

Surgical treatments are classified as ablative or physiologic.

- Ablative treatments

Ablative treatments do not address the underlying lymphatic dysfunction. They remove the compromised tissue, removing the subcutaneous tissue reaching the fascia (fascia is connective tissue that surrounds the whole body, in this procedure removal of skin could be included). This method addresses functionality of the limb and comfort levels. It is important to be aware that this surgery can be cosmetically unpleasant.

Suction-assisted lipectomy/liposuction is a preferred ablative method as it removes hydrophied fat in the affected area rather than skin tissue. This reduces the size of the affected area, does not require skin grafts and has minimal surface scaring. As ablative techniques do not address the underlying lymphatic dysfunction, compression garments must still be worn after surgery to help lymphatic flow.

- Physiologic treatments

Physiologic methods lik lymphatic bypass or lymphaticovenular anastomosis address lymphatic flow by redirecting fluid flow or introducing healthy lymphatic tissue to restore flow.

Lymphaticolymphatic bypass consists of taking healthy tissue from low limbs and inserting it between lymphatic vessels around the obstruction to promote flow around the obstruction, bypassing the blockage. Risks with this method is the development of lymphedema in the donor area.

Lymphatic redirection methods, such as lymphaticovenular anastomosis (LVA) redirect lymphatic fluid to the blood circulatory system, which is able to circulate the additional fluid8. LVA consists of microsurgery connecting healthy lymphatic tissue around the congested lymphatic channels to the venous (blood circulatory) system. This allows lymph fluid to drain rather than getting blocked around the obstruction, increasing swelling. LVA studies 16 have reported great improvements in quality of life and swelling control, with 85% of patients being able to stop using compression garments. The positive effects were long term, reported even 10 years after surgery.

Important to remember

As lymphedema prevents lymph fluid (that carries important cells to fight off infection) from flowing in and out, affected areas are at higher risk of infection. Lymph fluid is also protein-rich, adding to the risk of infection as protein is an energy source for bacteria. Therefore it is crucial to be aware of the infection and possible sources of infection. A common lymphedema infection is cellulitis or lymphangitis. A bacterial infection of the deeper skin layers treated with antibiotics.

Lymphedema also predisposes the skin to breakdown. Skincare and hygiene is crucial.

Tips to reduce risk of infection:

- Keep area hydrated with lotion

- Wear gloves when doing manual work such as cleaning gardening

- You may experience loss of sensation in areas affected by lymphedema. Take extra care in these areas for scratches or bruises. If you want to shave use an electric shaver not a razor.

- Be aware of insect bites, prevent with insect repellent and mosquito nets

- Immediately disinfect any wounds in the affected area

- No injections in the affected area such as blood tests or vaccines

Future Research

Genetics

- Predisposing genetic factors are being investigated as possible risk factors for lymphedema. A case-control study of 188 BC patients identified a higher amount of the connexin-47 gene mutation in women who developed lymphedema17. Connexin-47 plays a role in the development of valves and its mutation could lead to dysfunction of the lymphatic system8.

- Mutations of the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-C (VEGF-C) have been found to cause some primary lymphedema. Application of targeted healthy VEGF-C to injured areas is theorised to promote the regeneration and growth of lymphatic tissues. Clinical trials are in progress18.

BCRL is a chronic condition that requires a multimodal management approach. Adherence to your treatment plan is of utmost importance to prevent lymphedema from progressing and symptoms to worsen.

Cording

Lymphatic cording, also referred to as axillary web syndrome (AWS), is a more common breast cancer treatment side effect than lymphedema, infection, or seroma (buildup of fluid in the surgical area) 19. Although the high prevalence, there is limited research on cording, leaving its cause and how it develops mostly unclear.

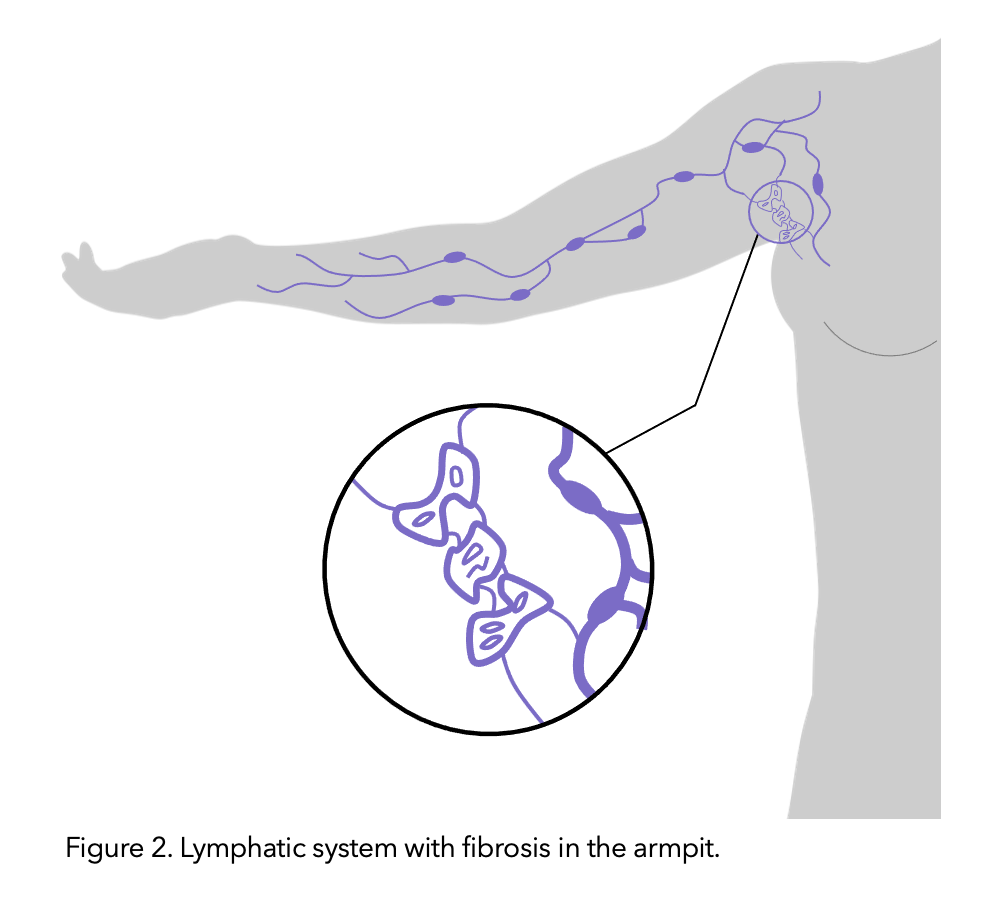

It is theorised that the lymphatic vessels connected to the removed nodes undergo fibrosis (thickening and hardening of skin due to tiny scar like structures caused by the protein rich lymph fluid which is stagnant/not draining). Like lymphedema, risk increases with the amount of disruption to the lymphatic system’s function.

One important difference is that cording can be treated and cured. With appropriate physiotherapy and exercises, most cases of cording can resolve.3

Figure modified from healthline.

Symptoms of Cording

Cording can start manifesting with tightness in the chest and arms, pain in movements and restriction in movements due to pain.

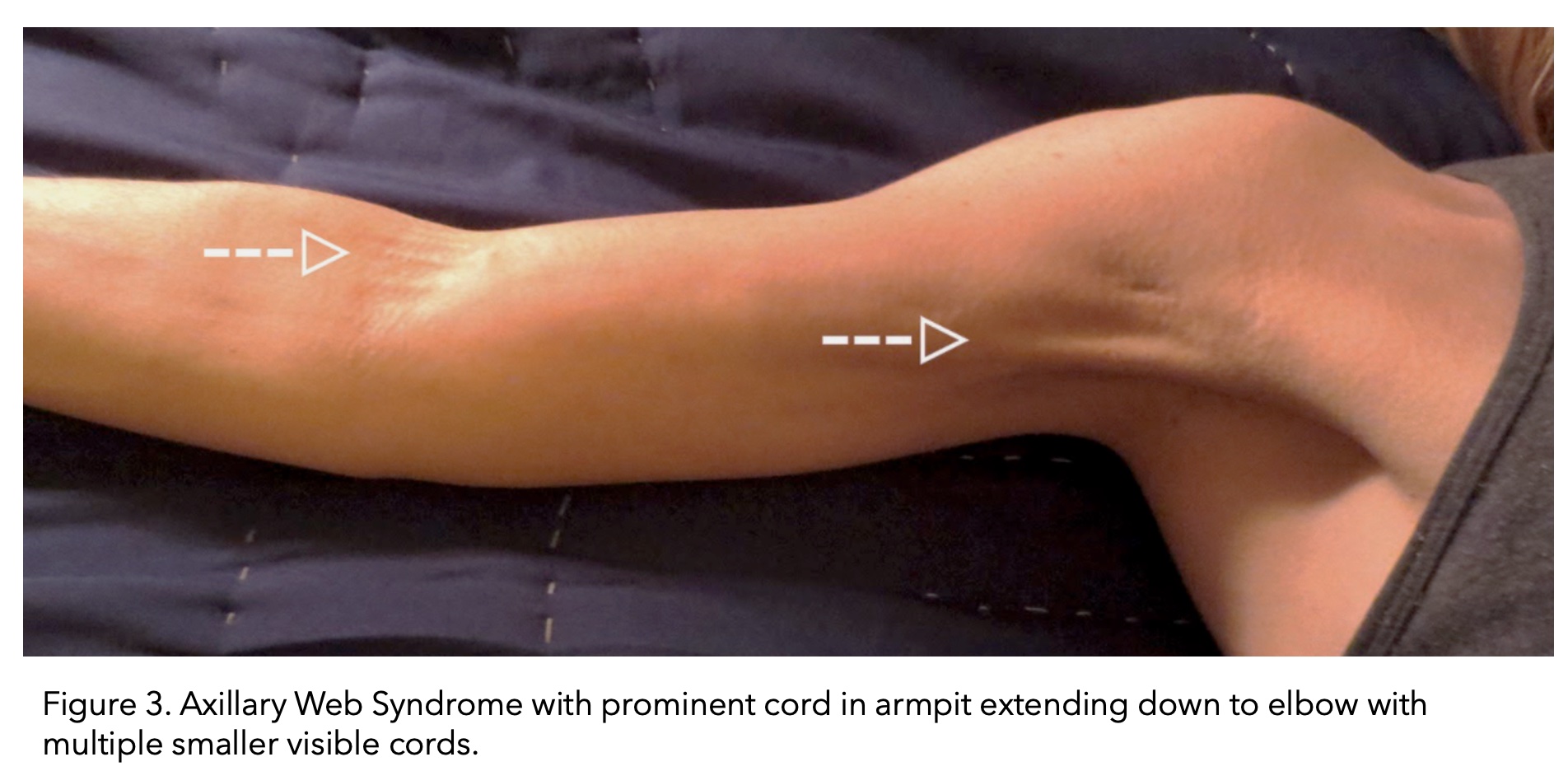

Cording can become visible and palpable, resembling a ropelike structure. Alternatively, multiple smaller chords can also form. Cording forms in the armpit area (axilla) and can extend down the arm all the way to the wrist.

Image taken from (The American Journal of Medicine, 2017).

Cording can be confused with scar tissue at the site of surgery. However, cording extends beyond the surgical site as it develops along the lymphatic vessels.

“It’s important not to ignore the early signs – tightness, sensation that something might snap, limited/restricted movement and to ask for help and referral to physiotherapy” – Mandy, OWise User

Cording most commonly develops 2–8 weeks following breast cancer surgery 20-22 but can occur months to years later. It can also resolve and then form again 22.

Cording incidence rates vary widely (6-86%). 1, 22,-24 This is in part due to the varying degrees in which breast cancer treatment can affect the lymphatic system.

Similarly to lymphedema, the incidence is higher in ALND surgery (36%–72%) compared with SLNB surgery (11%–58%)20-24. A meta-analysis reported a 3-4 time greater AWS incidence in ALND patients then SLNB patients.4

SLNB and ALND also affect the severity of cording and movement restriction. Restricted shoulder motion was reported to be 16% in cording patients who underwent SLNB compared to 64% of cording patients who received ALND in addition to SLNB. 23

Having preventative surgery of the opposite breast (contralateral prophylactic mastectomy) increases the risk of developing cording, with an incidence rate of (86%) 25

Cording Diagnosis

- Visible or palpable chord/s

- Restricted range of movement in upper body parts, especially shoulder and elbow movement.

- Moving the shoulder into maximal abduction (straight arm up over the head) can make the chords appear more evident

Referral to a physiotherapist before the cord becomes visible is recommended. Lack of treatment can lead to lifelong mobility issues and pain.

Treatment

“My self help measures were applying heat – a warm flannel or soaking in the bath/shower” – Mandy, OWise User

Standard treatment for cording consists of physical therapies.

Exercises and massages aimed at stretching and softening the cord and strengthening the surrounding muscles. These can be painful, your physiotherapist may recommend pain medication before physical therapies.

A cording experience

“I first noticed cording in my armpit 3 months after my mastectomy and breast reconstruction in September 2019 and did not know anything about cording until it appeared one day!

Post mastectomy surgery, the physio gave me exercises to do daily at home. I would advise any woman who has had any sort of breast surgery, to do them religiously.

The cording was a tight, painful string in my armpit and was very painful, I could see it protruding under my skin. I contacted my breast care nurse and she advised to stretch the area daily and massaging the area would help.

I do yoga most days and the gentle stretching helped with the cording. I found if I stretched beyond the pain it really gave me relief. Sometimes I heard a little ‘pop’ that is the tissue releasing.

I also used bio oil to massage over the cording, this was also helpful. The cording eventually went of its own accord.

I finished my radiation in January. Fast forward to February 2020. The cording returned, but it had moved down the inside of my upper arm to the inside elbow.

I finished my radiation in January. Fast forward to February 2020. The cording returned, but it had moved down the inside of my upper arm to the inside elbow.

Again I stretched until it was painful, held that stretch for a few seconds and massaged every day.

This time the ‘popping’ sensation of the cording releasing actually resulted in bruising to the inside of my elbow (figure 5). Again, it eventually righted itself.

I truly believe yoga stretches are invaluable, I do 10 minutes twice a day, morning and evening.

In conclusion, I think cording is something that comes and goes of its own accord but if it’s persistent, contact your breast team and they will arrange an appointment for the physiotherapist.”

– Khadija, OWise User

Evidence-based research into physical therapies for AWS treatments is still limited. However, there are reports of significant improvements to the quality of life, pain, arm function and movement. 26, 27

“Go to a physiotherapist ASAP and have them break it apart. Make sure you have someone who is specifically trained in this area. Once those cords are broke it makes a world of difference in getting your range of motion back and eliminating pain.” – Beacon Bragg, Co-founder and OWise User

AWS is important to treat as a restricted range of movement could interfere with you being able to position yourself to receive adjuvant (after surgery) radiotherapy. For example, a common treatment position is laying on your back with your hand laying above your head. Cording can restrict your ability to enter and remain in this position.

It is important to continue educating yourself on symptoms and looking out for these side effects as they can develop even after surgical follow-ups have completed.

If you are worried about any symptoms after your surgery please speak to your breast care nurse, doctor or physiotherapist.

If you are worried about any symptoms after your surgery please speak to your breast care nurse, doctor or physiotherapist.

Did you know you can track your lymphedema symptoms in the OWise app using the notes function in your diary!

Using the app you can track over 30 trends daily. Simply input how you’re feeling each day using the sliders, and then view how things develop over time by checking out the graphs. You can even share this with your care team or with a loved one.

Download OWise for free today!

References

- Harris, S.R., 2018. Axillary web syndrome in breast cancer: a prevalent but under-recognized postoperative complication. Breast Care, 13(2), pp.129-132.

- Wariss, B.R., Costa, R.M., Pereira, A.C.P.R., Koifman, R.J. and Bergmann, A., 2017. Axillary web syndrome is not a risk factor for lymphoedema after 10 years of follow-up. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(2), pp.465-470.

- Yeung, W.M., McPhail, S.M. and Kuys, S.S., 2015. A systematic review of axillary web syndrome (AWS). Journal of cancer survivorship, 9(4), pp.576-598.

- DiSipio, T., Rye, S., Newman, B. and Hayes, S., 2013. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet oncology, 14(6), pp.500-515.

- Lymphedema (PDQ®)–Patient Version. Retrieved March 10, 2021, from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/lymphedema/lymphedema-pdq

- Ayre K, Parker C. Lymphedema after treatment of breast cancer: a comprehensive review. J Unexplored Med Data 2019;4:5. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2572-8180.2019.02

- Wolfs, J., Beugels, J., Kimman, M., de Grzymala, A.A.P., Heuts, E., Keuter, X., Tielemans, H., Ulrich, D., van der Hulst, R. and Qiu, S.S., 2020. Protocol: Improving the quality of life of patients with breast cancer-related lymphoedema by lymphaticovenous anastomosis (LVA): study protocol of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 10(1).Garza, R., Skoracki, R., Hock, K. and Povoski, S.P., 2017. A comprehensive overview on the surgical management of secondary lymphedema of the upper and lower extremities related to prior oncologic therapies. BMC cancer, 17(1), pp.1-18.

- Campisi, C. and Boccardo, F., 2004. Microsurgical techniques for lymphedema treatment: derivative lymphatic-venous microsurgery. World journal of surgery, 28(6), pp.609-613.

- Boris, M., Weindorf, S. and Lasinkski, S., 1997. Persistence of lymphedema reduction after noninvasive complex lymphedema therapy. Oncology (Williston Park, NY), 11(1), pp.99-109.

- Tan, I.C., Maus, E.A., Rasmussen, J.C., Marshall, M.V., Adams, K.E., Fife, C.E., Smith, L.A., Chan, W. and Sevick-Muraca, E.M., 2011. Assessment of lymphatic contractile function after manual lymphatic drainage using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 92(5), pp.756-764.

- Lasinski, B.B., 2013, February. Complete decongestive therapy for treatment of lymphedema. In Seminars in oncology nursing (Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 20-27). WB Saunders.

- Fu, M.R., 2014. Breast cancer-related lymphedema: Symptoms, diagnosis, risk reduction, and management. World journal of clinical oncology, 5(3), p.241.

- Mortimer, P.S., 2000. Swollen lower limb—2: Lymphoedema. Bmj, 320(7248), pp.1527-1529.

- Brorson, H. and Svensson, H., 1998. Liposuction combined with controlled compression therapy reduces arm lymphedema more effectively than controlled compression therapy alone. Plast Reconstr Surg, (102), pp.1058-1067.

- Campisi, C., Bellini, C., Campisi, C., Accogli, S., Bonioli, E. and Boccardo, F., 2010. Microsurgery for lymphedema: clinical research and long‐term results. Microsurgery: Official Journal of the International Microsurgical Society and the European Federation of Societies for Microsurgery, 30(4), pp.256-260.

- Finegold, D.N., Baty, C.J., Knickelbein, K.Z., Perschke, S., Noon, S.E., Campbell, D., Karlsson, J.M., Huang, D., Kimak, M.A., Lawrence, E.C. and Feingold, E., 2012. Connexin 47 mutations increase risk for secondary lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. Clinical Cancer Research, 18(8), pp.2382-2390.

- Schindewolffs, L., Breves, G., Buettner, M., Hadamitzky, C. and Pabst, R., 2014. VEGF‐C improves regeneration and lymphatic reconnection of transplanted autologous lymph node fragments: An animal model for secondary lymphedema treatment. Immunity, inflammation and disease, 2(3), pp.152-161.

- Maldonado, S.N., Núñez, V.P., Vázquez, S.A., Cortiñas, M.M. and Morell, Á.R., 2016. Axillary web syndrome following sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer. Revista Española de Medicina Nuclear e Imagen Molecular (English Edition), 35(5), pp.325-328.

- Koehler, L.A., Blaes, A.H., Haddad, T.C., Hunter, D.W., Hirsch, A.T. and Ludewig, P.M., 2015. Movement, function, pain, and postoperative edema in axillary web syndrome. Physical therapy, 95(10), pp.1345-1353.

- Moskovitz, A.H., Anderson, B.O., Yeung, R.S., Byrd, D.R., Lawton, T.J. and Moe, R.E., 2001. Axillary web syndrome after axillary dissection. The American journal of surgery, 181(5), pp.434-439.

- O’Toole, J., Miller, C.L., Specht, M.C., Skolny, M.N., Jammallo, L.S., Horick, N., Elliott, K., Niemierko, A. and Taghian, A.G., 2013. Cording following treatment for breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment, 140(1), pp.105-111.

- Leidenius, M., Leppänen, E., Krogerus, L. and von Smitten, K., 2003. Motion restriction and axillary web syndrome after sentinel node biopsy and axillary clearance in breast cancer. The American journal of surgery, 185(2), pp.127-130.

- Bergmann, A., Mendes, V.V., de Almeida Dias, R., e Silva, B.D.A., Ferreira, M.G.D.C.L. and Fabro, E.A.N., 2012. Incidence and risk factors for axillary web syndrome after breast cancer surgery. Breast cancer research and treatment, 131(3), pp.987-992.

- Koehler, L.A., Hunter, D.W., Blaes, A.H. and Haddad, T.C., 2018. Function, shoulder motion, pain, and lymphedema in breast cancer with and without axillary web syndrome: an 18-month follow-up. Physical therapy, 98(6), pp.518-527.

- da Luz, C.M., Deitos, J., Siqueira, T.C., Palú, M. and Heck, A.P.F., 2017. Management of axillary web syndrome after breast cancer: evidence-based practice. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, 39(11), pp.632-639.

- Cho, Y., Do, J., Jung, S., Kwon, O. and Jeon, J.Y., 2016. Effects of a physical therapy program combined with manual lymphatic drainage on shoulder function, quality of life, lymphedema incidence, and pain in breast cancer patients with axillary web syndrome following axillary dissection. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(5), pp.2047-2057.

- Andersen, L., Højris, I., Erlandsen, M. and Andersen, J., 2000. Treatment of breast-cancer-related lymphedema with or without manual lymphatic drainage: a randomized study. Acta Oncologica, 39(3), pp.399-405.

- McNeely, M.L., Magee, D.J., Lees, A.W., Bagnall, K.M., Haykowsky, M. and Hanson, J., 2004. The addition of manual lymph drainage to compression therapy for breast cancer related lymphedema: a randomized controlled trial. Breast cancer research and treatment, 86(2), pp.95-106.