Cancer-related cognitive dysfunction (CRCD) can affect 75% 1 of cancer patients and 35% 2 of cancer survivors. Also known as ‘chemo brain’ or ‘chemo fog’, CRCD refers to changes and worsening in a range of brain functions including attention, learning, memory, processing speed and psychological wellbeing such as mood and anxiety. CRCD is not exclusive to chemotherapy, other treatments can also cause brain function problems. 1

Cancer-related cognitive dysfunction (CRCD) can affect 75% 1 of cancer patients and 35% 2 of cancer survivors. Also known as ‘chemo brain’ or ‘chemo fog’, CRCD refers to changes and worsening in a range of brain functions including attention, learning, memory, processing speed and psychological wellbeing such as mood and anxiety. CRCD is not exclusive to chemotherapy, other treatments can also cause brain function problems. 1

Changes in severity of CRCD differ between individuals and within individuals across time and treatments. CRCD commonly increases as treatment dose increases1. CRCD can begin before cancer treatment starts or well after treatment has ended. CRCD derived symptoms can have no effects on daily life or can be severely impairing, affecting daily life and psychological wellbeing 1.

In this blog we will discuss CRCD symptoms, some current hypothesized causes of CRCD and possible pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. We hope this information will help you feel better equipped to understand and handle the cognitive changes which can occur with cancer.

What does cancer related cognitive dysfunction feel like, how does it manifest?

CRCD affects conscious and unconscious brain functions. You may start noticing issues with your short-term memory, such as forgetting where you placed objects or your day plans. You may find concentrating and multi-tasking more difficult or you may start struggling with finding the right words.

Words escape me. I know what I want to say. I KNOW it. But then…there’s a disconnect somewhere – OWise user

You may find it difficult to complete your usual activities and employment duties. All these changes can affect your sense of identity and esteem. It is important you talk to your loved ones, care team and employers about these changes so they can best support you.

Remember that everyone has lapses in memory and that everyone’s capabilities change on a daily basis. Changes are not always a result of your cancer or treatment. Be kind to yourself and your brain, take note of any changes to discuss with your care team to better understand what may be causing them. More on this later in the blog!

What causes cancer related cognitive dysfunction?

It is still not exactly clear how breast cancer and treatment harm brain function. There are many different mechanisms that underpin CRCD and multiple genetic and psychological theories are being investigated.

A study revealed that pretreatment Stage 1-3 breast cancer patients were more likely to perform worse before treatment than Stage 0 patients and healthy controls 3 (to learn more about Stages, check out this post). This indicates there are important factors relating to the cancer itself and to emotional wellbeing which can influence cognitive function before treatment does.

These can include psychological and emotional strain. It is well documented that stress, anxiety and depression impair cognitions4. These challenging internal states ‘take over’ available cognitive resources resulting in less resources being available to complete brain functions such as memory encoding and recollection (making and remembering memories). 5, 6 This can manifest itself as poor short-term memory. For example, something as simple as forgetting where you left your keys or someone’s name.

Indeed studies with breast cancer patients have found significant associations between depression and CRCD7. Talk to your doctor if you are experiencing severe changes in mood and stress. There are many support options including psychological therapies. Find out more in our useful links at the end of this blog.

Genetic predispositions that can increase vulnerability to CRCD

You may be born with certain genetic characteristics which make you more prone to CRCD. This does not mean you will for certain experience CRCD if you have these predispositions, just as you may experience CRCD even without these predispositions.

Various genes are being investigated for their possible role in CRCD. For example, COMT genes regulate neurotransmitters which help brain cells communicate with each other while BDNF and APOE genes play a role in neural repair and growth. Differences in these genes can increase the risk of cognitive dysfunction 8.

A group of genetic variations have been associated with impairments in cell DNA repair mechanisms9. It is not unusual for DNA to become damaged and cellular repair mechanisms usually fix the cell, allowing it to continue functioning as it should. However, having this group of genetic variations can alter these repair mechanisms which can increase the risk of cells not functioning properly, leading to cognitive dysfunction.

What are some cancer drug mechanisms behind CRCD?

Brain cell damage: Structural changes in the brain

Chemotherapy can damage DNA in cells, accelerating cell aging and hindering cell growth 10. Processes involved in repairing 9 DNA can also be affected by chemotherapy. This can result in an accumulation of DNA damage that can accelerate the death of neurons (cells in the brain). This would impair brain plasticity (how the brain grows, learns and adapts) leading to issues with various brain functions.

Most cancer treatments aim to stop cell division, however they do not only target cancer cells, healthy cells are affected as well. This causes a reduction in cell division, particularly in the hippocampus11, reducing its size and functioning, causing memory problems.

Neuroplasticity is well-recognised today. However, up until the 60s scientists did not believe in this and it was a female neuroscientist, Marian Diamond, who was one the first to demonstrate in 1964 that the adult brain can change.12

(Cool fact: she was the scientist who analysed Einstein’s brain!)

Chemotherapy drugs also interfere with the number of cortical spines and dendrites, which are brain structures that make up white and grey brain matter and transport electrical brain signals13. This is how the brain communicates and passes on instructions. Grey matter is integral to focus, working memory, executive functioning (completing tasks) and verbal ability. White matter is important for focus and processing speed. A reduction in these structures leads to a reduction in their functions.

Inflammation and the blood-brain barrier

Our brain has a blood barrier, a layer of cells that protects the brain from harmful agents like viruses and bacteria, and partially from treatments such as chemotherapy. However, research shows that many chemotherapy drugs such as methotrexate, fluorouracil or platinum based drugs, can pass this barrier and enter the brain14. As previously discussed, chemotherapy drugs can cause brain cell death, but can also activate inflammatory processes 15, 16.

Inflammation is the body’s biological response to harmful agents. Chemotherapy drugs can trigger inflammatory processes that activate brain cells (microglia and astrocytes) and immune cells (T and B cells) prompting them to produce cytokines 17 12. Cytokines are messenger proteins that can amplify the inflammation and potentially damage brain cells and thereby their function. For example, studies show that high levels of certain cytokines such as TNF can reduce the functionality of the hippocampus, which is a brain area in charge of our memory 18. Moreover, studies found associations between the levels of TNF and subjective memory complaints in breast cancer survivors 15 and in cancer patients after treatment 15. Cytokines can also also affect the structure of the blood–brain barrier, allowing the entrance of more proinflammatory cytokines and chemotherapeutic drugs 13.

Are there changes in objective brain functioning? Is the brain communicating with itself differently?

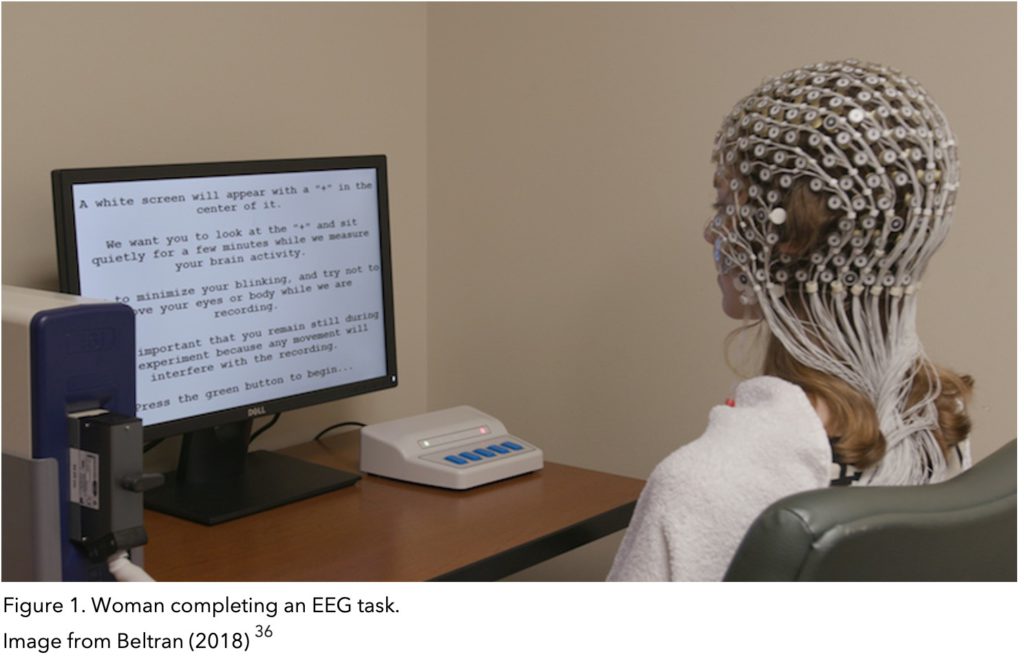

Studies have revealed abnormal brain activation in breast cancer patients who report CD. EEG findings indicate difficulty in sustained attention, different resource allocation and brain patterns indicative of increased mind wandering 19. Mind-wandering, which is the greater and debilitating amount of thoughts intruding on focus, could underpin concentration issues and difficulties with completing tasks.

Electroencephalogram (EEG) is a technique used to study brain functioning by recording the electrical signals your brain cells (neurons) send each other to communicate. To do this electrical sensors that pick up your brain’s electrical signals are placed around your scalp (see figure 1). The procedure is non-invasive and painless. No electricity is passed onto your body.

Can I be diagnosed with CRCD?

There is still no gold standard assessment to provide a CRCD diagnosis. Clinicians and researchers rely on patient and caregiver self-report measures. A commonly used measure is the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT-Cog) which was created specifically to measure cognitive dysfunction in people affected by cancer. The questionnaire investigates perceived cognitive impairments and abilities, comments others make on impairments and abilities and impact on quality of life. You can access the questionnaire here. 20

What interventions are there for CRCD?

Symptoms of CRCD can be managed to limit their impact on daily life and overall quality of life. They can also be targeted to prevent worsening and promote recovery. These interventions can be very effective as the brain is plastic, meaning it’s malleable and able to learn and recover very efficiently.

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

Non-pharmacological interventions consist of compensatory strategies and cognitive rehabilitation methods.

Compensatory strategies

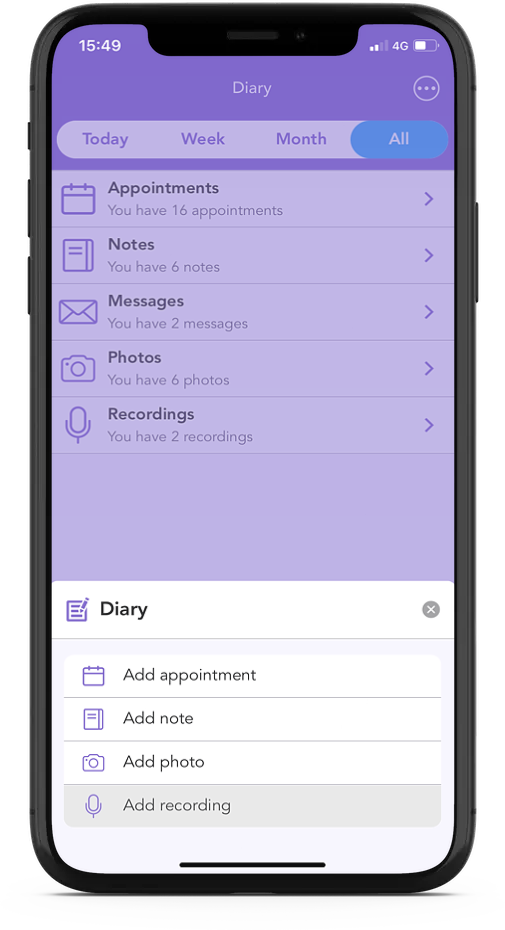

Compensatory strategies can be used to overcome limitations caused by CRCD. Tools such as diaries and technology can be used to keep track of tasks, how to complete them, as well as offer visual and auditory cues.

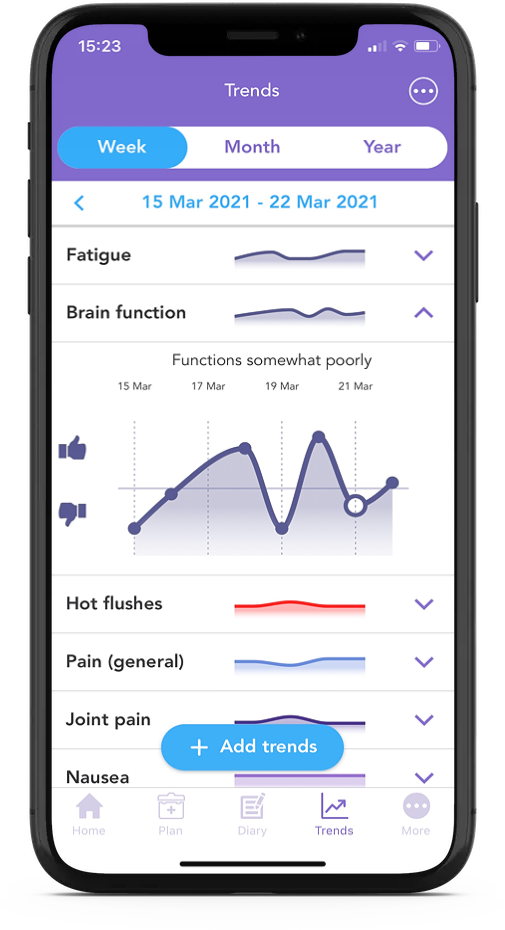

With OWise you can track your daily Brain function and have an overview of any changes. You can easily share these with your care team to help create compensatory strategies tailored to your needs.

Cognitive Rehabilitation

Cognitive training

Cognitive training aims to enhance brain plasticity, which is how effectively the brain can grow, adapt and learn. Much like physical exercises, cognitive training consists of exercises that when performed strengthen brain connections (like strengthening muscle connection). These increase brain plasticity and functioning. Cognitive training exercises can include activities such as sudoku and crosswords. BrainHQ, built by neuroscientists, offers a wide range of exercises whose benefits have been scientifically proven in a wide range of domains 21, 22.

EEG biofeedback

EEG biofeedback is an approach which aims to address the underlying brain functioning issues and restore optimal functioning. With EEG technology brain activity is monitored and desirable brain wave patterns are reinforced by visual or auditory cues 23. This strengthens subconscious brain functions and promotes new neural pathways, improving brain performance.

An EEG biofeedback study of women who completed treatment for breast cancer and reported CRCD revealed significant improvements across biofeedback sessions in four cognitive outcomes measured by the FACT-Cog (perceived cognitive impairment, perceived cognitive abilities, comments from others on functioning, and impact on quality of life). As well as fatigue, depression, anxiety, and sleep. These improvements were still present four weeks after the last biofeedback session 24. Speak to your care team about available EEG biofeedback options in your area.

Cognitive-behavioral approaches

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

CBT is a well established form of structured therapy which aims to restructure thoughts, emotions, attitudes and behaviors to encourage adaptive and successful functioning. CBT is first-line therapy for many psychological issues, including depression and anxiety, which influence CRCT. Consequently, CBT will bring about positive change by influencing CRCT directly but also by improving depression and anxiety which will, in turn, improve CRCD. CBT is also a treatment option for non-psychological conditions, such as chronic pain. 25, 26

CBT for chronic pain does not decrease absolute levels of pain but aims to help restructure how pain and its limitations are perceived and dealt with. CBT with chronic pain patients improved various parts of life including social, emotional, physical movement and occupation. Leading to overall improved quality of life. 21, 27, 28

These CBT principles can be applied by individuals experiencing CRCD to restructure how they perceive and cope with the limitations brought on by the CRCD. Inform yourself with your insurance provider on available CBT options or speak with your care team for free or reduced options available in the hospital or local area.

Memory and Attention Adaptation Training (MAAT)

Memory and Attention Adaptation Training (MAAT) is a cognitive behavioral approach created specifically to target cognitive dysfunction. It is based on four components and delivered over an eight week period of 50min sessions. It aims to minimize the impact of cognitive change on quality of life. 29

1.Education

Learn about cancer related cognitive problems as well as other non cancer related factors which could influence cognition. These could be environmental factors (visual or auditory overload) or internal states (stress, anxiety, depression, hunger, fatigue). If dysfunctions can be attributed to non cancer factors they can be targeted to improve.

2. Self-awareness training

Understand what situations are ‘high risk’ for cognitive issues. Record incidents in which you did not perform as well as you may have wanted. Note the environment you are in and your internal state. For example, were you in a loud room or were you stressed from running late. Stressors can also be less obvious. For example, you may be subconsciously worried as you are waiting for results. At the end of the day evaluate how much distress each incident caused and what type of brain function did not work properly. For example, did you forget a word or how to complete a task?

A record of struggles and lapses in performance will help you figure out your ‘high risk’ situations and any patterns in issues surrounding your brain function. This will be useful when choosing which compensatory strategies would be most useful to implement.

The OWise app is the perfect place to record all of this information and share it securely with your care team.

3. Self-regulation

Learn to self-regulate emotions and bodily reactions that can interfere with brain functioning (eg stress and anxiety). These are some useful tips:

- Bodily relaxation methods such as

- Breathing

- Mindfulness

- Pacing

- Exercise can enhance many brain functions. Aerobic exercise can increase the number of cells in the hippocampus (brain area in charge of memory) 30 and can improve attention and reaction times 31. A clinical trial with breast cancer survivors revealed that after aerobic exercise reaction times decreased and spatial memory was better 32.

- Scheduling/ planning your day

- Setting achievable goals to feel accomplished

- Scheduling enjoyable activities that will improve your mood. Remember, improved mood enhances performance 21 so take time for self-care.

4. Compensatory strategies

Behavioral or cognitive skills and external tools to help prevent and minimize impact of lapses in brain functioning.

- Verbal repetition to help create a memory/learning (eg a phone number)

- Verbal repetition to hold a thought and information in mind long enough to complete the task (eg call the number)

- Space rehearsal : gradually increase the interval at which you verbally repeat

- Self-instructional training (SIT): verbally guide yourself through completing a task. Helps stay on task and not forget any steps. Especially helpful with procedural tasks.

External tools such as OWise can help with note keeping, auditory and visual cues and reminders.

MAAT has been scientifically tested with breast cancer patients and survivors. A study evaluated its efficacy when delivered via video call. Participants reported improvements in cognitive impairments, processing speed, general function, fatigue and anxiety. These improvements lasted after completion of the program, with significant effects at the 2 month follow-up 29.

These results are very promising as they indicate MAAT to be a successful approach which can be delivered remotely. This circumvents mobility and access issues and means successful interventions can be delivered across the country irrespective of location and resources. This is increasingly important nowadays due to the limitations we face from the COVID-19.

Pharmacological Interventions

A small trial with breast cancer patients reported positive effects of modafinil on memory and attention 33. Participants improved in quality of memories, speed of remembering and ability to maintain attention. More studies on the use of stimulants are needed but results are promising.

Future studies will also examine the possibility of combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to leverage the effects of pharmacological treatments to enhance non-pharmacological strategies.

To conclude…

It is important to approach CRCD treatment holistically and long term as various factors can influence cognition. Mental health should be a key pillar in this holistic treatment due to its significant effects on cognition and overall quality of life.

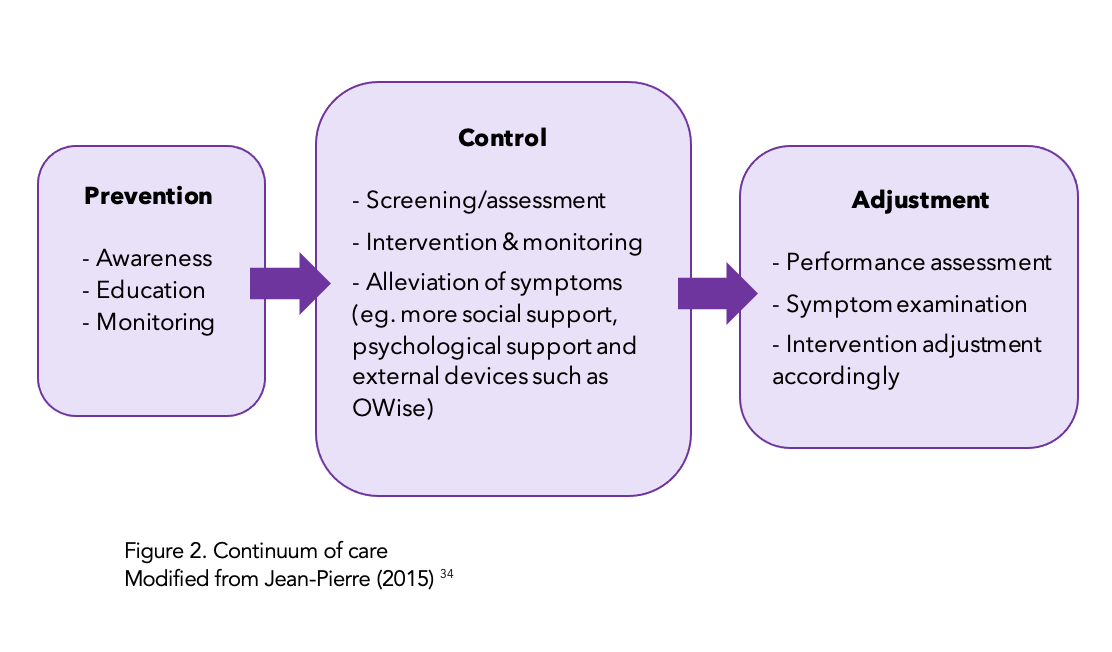

The continuum of care (fig 2) outlines a longitudinal approach to the management of CRCD. 34

Studies investigating cognitive rehabilitation programs revealed that programs in which patients can report their own cognitive symptoms were associated with significant improvements in anxiety, depression and fatigue. 35

So remember to track your brain function with the OWise trend feature and keep track of any cognitive changes and difficulties you encounter.

With OWise you can keep track of appointments, tasks you need to complete and jot down any important information so you don’t forget. It’s stored all in one place, so it’s easy to find and share with your care team if you need any extra support!

Did you know you can take and store photos and audio recordings in the OWise app? Learn how here

We hope that you now better understand your treatment options and can feel confident in discussions with your care team. Our aim is to make sure you are kept informed so make sure to follow our Instagram and Twitter accounts for any updates.

Helpful resources for online cognitive training:

Helpful resources:

- https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivors/life-after-cancer/talk-to-someone-simulation.htm

- https://cbtonline.com/

References

- Jean-Pierre, Pascal. “Management of cancer-related cognitive dysfunction—conceptualization challenges and implications for clinical research and practice.” US oncology 6 (2010): 9.

- Janelsins, Michelle C., et al. “Prevalence, mechanisms, and management of cancer-related cognitive impairment.” International review of psychiatry 26.1 (2014): 102-113.

- Ahles, Tim A., et al. “Cognitive function in breast cancer patients prior to adjuvant treatment.” Breast cancer research and treatment 110.1 (2008): 143-152.

- Millan, Mark J., et al. “Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy.” Nature reviews Drug discovery 11.2 (2012): 141-168.

- Kircanski, Katharina, Jutta Joormann, and Ian H. Gotlib. “Cognitive aspects of depression.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 3.3 (2012): 301-313.

- Ellis, H. C., et al. “Affect, cognition and social behaviour.” Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Hogrefe (1988): 25-43.

- Hermelink, Kerstin, et al. “Two different sides of ‘chemobrain’: determinants and nondeterminants of self‐perceived cognitive dysfunction in a prospective, randomized, multicenter study.” Psycho‐oncology 19.12 (2010): 1321-1328.

- Simó, Marta, et al. “Chemobrain: a systematic review of structural and functional neuroimaging studies.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 37.8 (2013): 1311-1321.

- Goode, Ellen L., Cornelia M. Ulrich, and John D. Potter. “Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes and associations with cancer risk.” Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 11.12 (2002): 1513-1530.

- Zglinicki, T. V., and C. M. Martin-Ruiz. “Telomeres as biomarkers for ageing and age-related diseases.” Current molecular medicine 5.2 (2005): 197-203.

- Pereira Dias, Gisele, et al. “Consequences of cancer treatments on adult hippocampal neurogenesis: implications for cognitive function and depressive symptoms.” Neuro-oncology 16.4 (2014): 476-492.

- Diamond, Marian C., David Krech, and Mark R. Rosenzweig. “The effects of an enriched environment on the histology of the rat cerebral cortex.” Journal of Comparative Neurology 123.1 (1964): 111-119.

- Nguyen, Lien D., and Barbara E. Ehrlich. “Cellular mechanisms and treatments for chemobrain: Insight from aging and neurodegenerative diseases.” EMBO molecular medicine 12.6 (2020): e12075.

- Wefel, Jeffrey Scott, Robert Collins, and Anne E. Kayl. “Cognitive dysfunction related to chemotherapy and biological response modifiers.” Cognition and cancer (2008): 97-114.

- Vichaya, Elisabeth G., et al. “Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced behavioral toxicities.” Frontiers in neuroscience 9 (2015): 131.

- Janelsins, Michelle C., et al. “Prevalence, mechanisms, and management of cancer-related cognitive impairment.” International review of psychiatry 26.1 (2014): 102-113.

- Pusztai, Lajos, et al. “Changes in plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines in response to paclitaxel chemotherapy.” Cytokine 25.3 (2004): 94-102.

- Maier, Steven F., and Linda R. Watkins. “Immune-to-central nervous system communication and its role in modulating pain and cognition: Implications for cancer and cancer treatment.” Brain, behavior, and immunity 17.1 (2003): 125-131.

- Kam, J. W. Y., et al. “Sustained attention abnormalities in breast cancer survivors with cognitive deficits post chemotherapy: an electrophysiological study.” Clinical Neurophysiology 127.1 (2016): 369-378.

- URL

- Ferguson, Robert J., and Amber A. Martinson. “An overview of cognitive-behavioral management of memory dysfunction associated with chemotherapy.” Psicooncologia 8.2/3 (2011): 385.

- Smith, Glenn E., et al. “A cognitive training program based on principles of brain plasticity: results from the Improvement in Memory with Plasticity‐based Adaptive Cognitive Training (IMPACT) Study.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57.4 (2009): 594-603.

- Luctkar-Flude, Marian F., Jane Tyerman, and Dianne Groll. “Exploring the use of neurofeedback by cancer survivors: Results of interviews with neurofeedback providers and clients.” Asia-Pacific journal of oncology nursing 6.1 (2019): 35.

- Alvarez, Jean, et al. “The effect of EEG biofeedback on reducing postcancer cognitive impairment.” Integrative cancer therapies 12.6 (2013): 475-487.

- Rohling, Martin L., et al. “Effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: a meta-analytic re-examination of Cicerone et al.’s (2000, 2005) systematic reviews.” Neuropsychology 23.1 (2009): 20.

- Cicerone, Keith D., et al. “Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: recommendations for clinical practice.” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 81.12 (2000): 1596-1615.

- Turk, Dennis C., and Tasha M. Burwinkle. “Clinical Outcomes, Cost-Effectiveness, and the Role of Psychology in Treatments for Chronic Pain Sufferers.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 36.6 (2005): 602.

- Morley, Stephen, Christopher Eccleston, and Amanda Williams. “Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache.” Pain 80.1-2 (1999): 1-13.

- Ferguson, Robert J., et al. “A randomized trial of videoconference‐delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for survivors of breast cancer with self‐reported cognitive dysfunction.” Cancer 122.11 (2016): 1782-1791.

- Liu, Patrick Z., and Robin Nusslock. “Exercise-mediated neurogenesis in the hippocampus via BDNF.” Frontiers in neuroscience 12 (2018): 52.

- Tsai, Chia-Liang, et al. “Impact of acute aerobic exercise and cardiorespiratory fitness on visuospatial attention performance and serum BDNF levels.” Psychoneuroendocrinology 41 (2014): 121-131.

- Salerno, Elizabeth A., et al. “Acute aerobic exercise effects on cognitive function in breast cancer survivors: a randomized crossover trial.” BMC cancer 19.1 (2019): 1-9.

- Kohli, S., et al. “The cognitive effects of modafinil in breast cancer survivors: A randomized clinical trial.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 25.18_suppl (2007): 9004-9004.

- Jean-Pierre, Pascal. “Management of cancer-related cognitive dysfunction—conceptualization challenges and implications for clinical research and practice.” US oncology 6 (2010): 9.

- Bray, Victoria J., et al. “Evaluation of a web-based cognitive rehabilitation program in cancer survivors reporting cognitive symptoms after chemotherapy.” (2017).

- Beltran, James. “National Trial: EEG Brain Tests Help Patients Overcome Depression.” UT Southwestern Medical Center, www.utsouthwestern.edu/newsroom/articles/year-2018/eeg-brain-tests.html.